“The stories that Josué Sánchez tells in his paintings seem to unfold from the Andean sky. Ancient spirits fight and dance in the lightning as his narratives tumble down the terraced mountainsides into villages inhabited by Quechua-speaking ghosts, and then trickle into underground realms where copper miners mingle with subterranean gods. These men seem to be in league with the spirits, extracting precious metals to be sold across the world. His stories resurface through freshwater springs pouring into the Amazon jungle, where in the swampy undergrowth, a white phantom reclines on the back of a puma gently caressing the passing jungle flora. In the worlds that the artist creates geological layers allude to the existence of alternate realities. The verticality of the Andes hints at the passage of time, of the new and the old interlocking in labyrinth- like architecture. Altitude determines the shape of life.

When I think of Josué Sánchez’s paintings these are some of the images that swirl in my head. I have been looking at his work for nearly 30 years, and I can still remember the first time I came across it. I was on a trip to Peru with my family in 1996. Josué had recently been commissioned to paint the central dining hall of the Convent of Santa Rosa de Ocopa, located in the province of Junín, in the central Andes. The convent was established by the Franciscans in 1725 as a center for missionaries seeking to convert the indigenous people of the Amazon Basin to Christianity. Josué’s mural covers the walls and ceiling of the hall, depicting life in the jungle with a lysergic radiance. I remember that we all gasped when we walked into the room. Amid all the vibrant colors and the flow of the verdant plant life, Josué had woven what at first appears to be the beautiful story of a harmonious encounter between the missionaries and the native peoples. Shamans conduct Ayahuasca ceremonies to commune with the spirits, giant flowers bloom around every light bulb socket, and monkeys climb the saturated jungle foliage, all the while Franciscan priests bring their religion. But tucked in the corner of the room, a double-headed leviathan lurks, twisting around a tree. The creature’s heads extend over and under a dark conclusion to this encounter—a scene of violent environmental destruction. The jungle has been slashed and burned, bombs fall from the sky, skulls litter the ground, and the disembodied head of a native person floats in the smoke of a fire. In contrast to Catholic theology, Josué’s mural suggests that hell is not something that exists in another dimension or the afterlife. Rather, it exists here on this plane, in this world; it is a consequence of the Franciscans’ encroachment on the Amazon and its people. The work also pulls the past into the present, connecting the two in such a way as to discredit the idea that the past is only behind us. The past lives with us, the mural contends. I took note of these subversive messages. Looking at this mural now, I realize how intertwined my own approach to artmaking is with this moment, with my own first encounter with Josué’s work in the Andes.

Two years later, after graduating from the San Francisco Art Institute, I was living with my family in Huancayo, which is Josué’s hometown. At the time, Josué was living on the outskirts of town in an adobe house he had constructed himself. The first time I visited him there, I was struck by the yard that was filled with his sculptures and surrounded by fields of potato and corn, where a woman in a beautifully woven manta was milking a cow. I was in one of his paintings. He welcomed me with a warm and soft voice. I was comforted by the way he spoke, by the sound of his lilt, something I associate with people from the mountains. This was the beginning of our friendship.

I spent nearly a year living in Huancayo and during that time Josué offered me a room to work in at his house, which became my studio of sorts. He introduced me to other artists in town, and I helped him with a mural he was working on with local children in the market. At the time, he was the director of the Casa de Cultura, a local cultural center, and he invited me to exhibit there. As I prepared my work for the exhibition, he would come into the studio and give me his feedback. We had great conversations with his wife Diana over coffee and toast, discussing art and politics and sharing stories from our lives. Josué would tell me stories about the folklore and traditions of the Huanca people, my father’s people. I would take breaks in the afternoon to play with his two-year-old son, Alvaro, in the grass among Josué’s sculptures. It was a beautiful time; it was nice to feel like I belonged.

When I reflect on my experiences during that year, I think of it as a crucial chapter in my development as an artist. I had just finished undergrad at SFAI, where I studied with another amazing artist, Carlos Villa. Through Carlos’ work and mentorship, I gained the confidence to look beyond the dominant narrative of Western art history. In a sense, Carlos gave me permission to look at my own culture, reorienting my perspective, something that I have come to refer to as “looking/listening south.” When I moved to Peru, I was looking south, searching. Josué became a direct link to my own artistic DNA, my own art history. He both expanded my understanding of a heritage of forms that I belonged to, while helping me find the path to develop my own visual language.

Josué also made a deep impression on the way that I use color. He taught me that it’s possible to create great complexity within a simple color palette. He also taught me how to create a rhythmic sense of space, using patterns and unexpected shifts of value to push objects into the background, or pull them into the foreground. I am constantly thinking of how a specific arrangement of colors and shapes can create atmospheric space, and thus a mood, an emotion.

When I first met Josué, like so many young artists, I was looking for guidance on how to be an artist. I was looking for someone that was not just “looking south” but “living south.” His paint carries the code of Peruvian rural life embedded in it. Josué speaks to his community, he speaks to our shared history and shared subconscious. When he paints an Amaru, an ancient Peruvian god, my heart responds to this creature. When he paints a flower, my body knows the land that flower grew in. He is an invaluable coordinate to me, helping me navigate my dreams and this world. This exhibition is important for that very reason, it is a rare opportunity to bridge the Americas through the worlds and stories Josué so vibrantly creates.” – Eamon Ore Giron

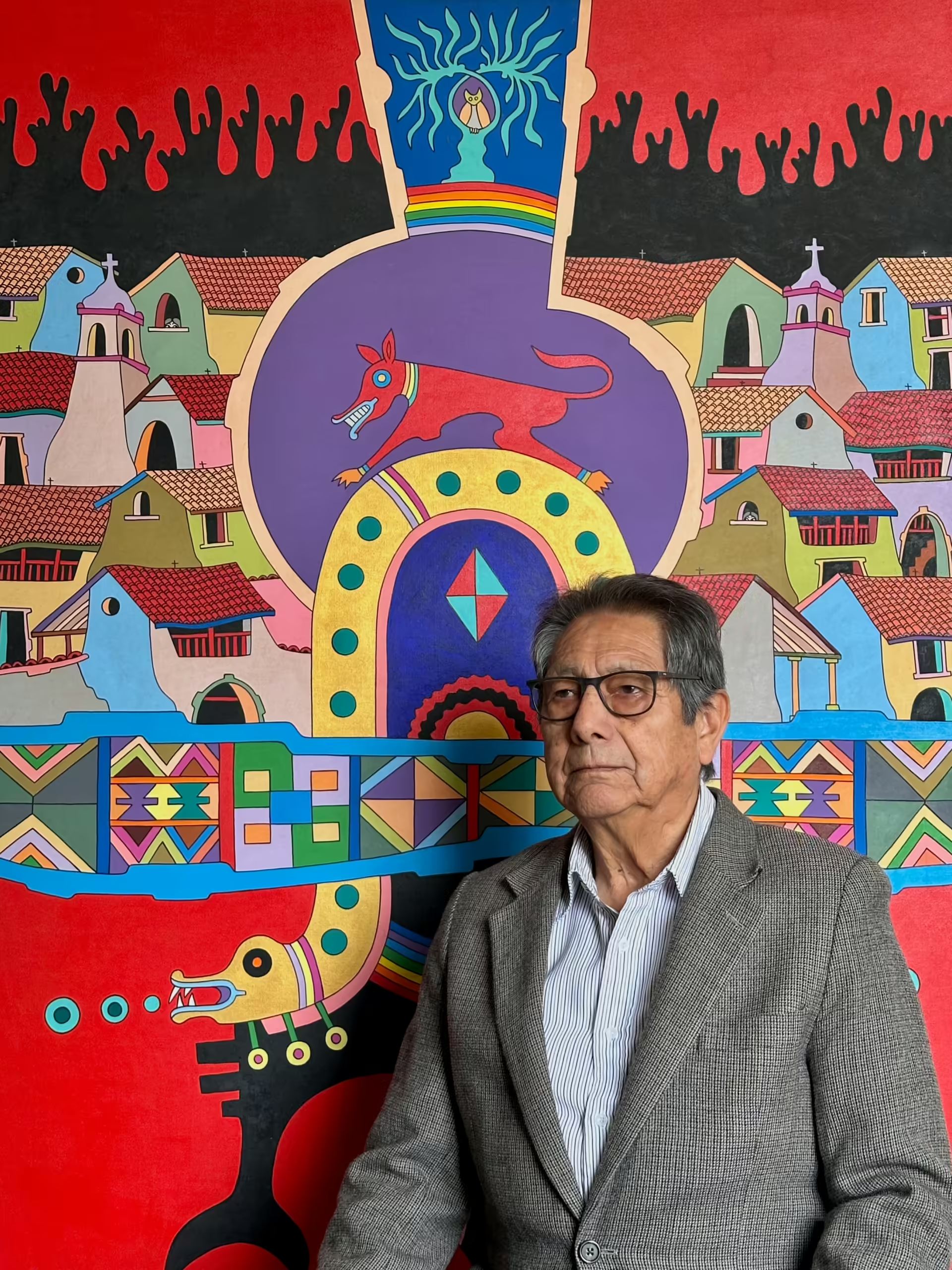

Guardians of the Sacred Land marks Josué Sánchez’s debut exhibition in the United States. It will be on view in our Upstairs Gallery through January 11th, 2025.