Hanging out with Katie Stout

Words by Tony Moxham, Photography by Kate Orne

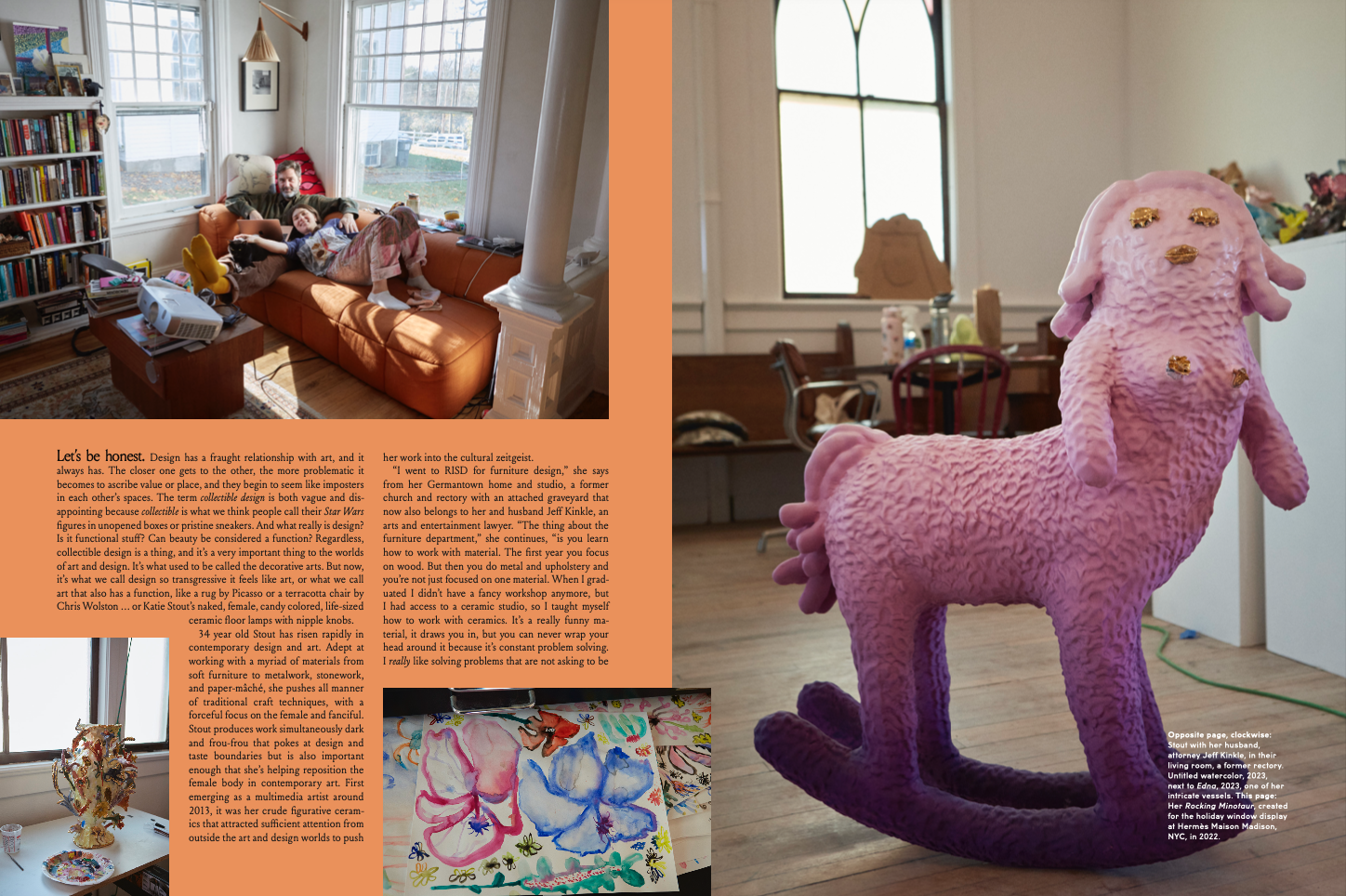

Let’s be honest. Design has a fraught relationship with art, and it always has. The closer one gets to the other, the more problematic it becomes to ascribe value or place, and they begin to seem like imposters in each other’s spaces. The term collectible design is both vague and disappointing because collectible is what we think people call their Star Wars figures in unopened boxes or pristine sneakers. And what really is design? Is it functional stuff? Can beauty be considered a function? Regardless, collectible design is a thing, and it’s a very important thing to the worlds of art and design. It’s what used to be called the decorative arts. But now, it’s what we call design so transgressive it feels like art, or what we call art that also has a function, like a rug by Picasso or a terracotta chair by Chris Wolston … or Katie Stout’s naked, female, candy colored, life-sized ceramic floor lamps with nipple knobs.

34 year old Stout has risen rapidly in contemporary design and art. Adept at working with a myriad of materials from soft furniture to metalwork, stonework, and paper-mâché, she pushes all manner of traditional craft techniques, with a forceful focus on the female and fanciful. Stout produces work simultaneously dark and frou-frou that pokes at design and taste boundaries but is also important enough that she’s helping reposition the female body in contemporary art. First emerging as a multimedia artist around 2013, it was her crude figurative ceramics that attracted sufficient attention from outside the art and design worlds to push her work into the cultural zeitgeist.

“I went to RISD for furniture design,” she says from her Germantown home and studio, a former church and rectory with an attached graveyard that now also belongs to her and husband Jeff Kinkle, an arts and entertainment lawyer. “The thing about the furniture department,” she continues, “is you learn how to work with material. The first year you focus on wood. But then you do metal and upholstery and you’re not just focused on one material. When I grad- uated I didn’t have a fancy workshop anymore, but I had access to a ceramic studio, so I taught myself how to work with ceramics. It’s a really funny material, it draws you in, but you can never wrap your head around it because it’s constant problem solving. I really like solving problems that are not asking to be solved. No one cares, but I’m here to solve them. And, yeah, ceramics offer up a lot of problems.”

After college Stout began working for Paul Johnson and his notorious Johnson Trading Gallery, pushing herself into the position of gallery director while at the same time working to fabricate work for other artists like Bjarne Melgaard, for whom she produced the majority of a Whitney Biennial installation in 2014. “I even fabricated some of it myself,” she says, “like these braided rugs and an insane sofa plus all these weird dolls. There was a person who covered stuff in hair extensions. It was really insane.” Stout began showing her own figurative ceramic objects at galler- ies like R & Company and Jeffrey Deitch, in Manhattan, and with Nina Johnson, in Miami, where, in December, she had an ambitious solo show during Design Miami. After working in Brooklyn for years though, she was becoming problematic. “I was going from studio to studio, constantly getting in trouble for firing something stinky in the kiln or working outside. So, we got this idea to move upstate so I could get a studio and we could live next to it. We found the perfect spot, a church and house. It’s only an acre, and half of it’s a graveyard. The most recent headstone is from the seventies … it’s sweet because someone comes by and puts flowers near it. There are the most insane pockets of people here. A lot of my friends are also artists or designers and I think one of the ways I connect with people is through making things with them. Or putting on an event. Jeff and I like to throw funny parties together. We recently had a talent show in the church. I want to start like a party line of crazy bounce houses and party paraphernalia.”

Ceramics are what largely propelled Katie’s artistic career, and what most people know and respond to from her oeuvre. She’s inspired a mass of copycat makers on platforms like Etsy and Instagram because she champions women and also shows what’s surprisingly possible by hand. Ceramics are a fickle mistress and what Katie makes pushes towards the limit of what can be done with clay. For that reason alone, her work is a ceramic flex, and that’s really cool. It’s energized with a palpable technical pride. But this technical prowess at times also overshadows Katie’s darker ideas, and overshadows Katie as artist. The naiveté of her technique overshadows her technical prowess. And her subject matter overshadows the seriousness of her intent and her ideas.

“Size fucking matters,” she says bluntly about ceramics. “The first Lady Lamps I made were table lamps but then I thought, I’m going to make floor lamp versions — I really wanted them to be confrontational. So, the on/off switch is the nipple and I’ve also done a butthole. I wanted to make them as kitsch as possible. I still get a feeling in my stomach after I do anything where I’m like, is this good? I have no conception about whether it’s good or bad or a waste of time.” When effort and investment in materials doesn’t equate with what sells it can be even more perplexing for an artist, or frankly for anyone running any business. “I just made water colors for Nina Johnson, and it was so easy and didn’t cost me anything. And they’re just selling. I feel confused, insulted, and also kind of pleased. But the large ceramic things that require love, labor, and attention will probably not sell so fast because they’re a hassle to move around.”

Which bring us back to the decorative arts. At best, folks today think of the decorative arts as the couture end of the design world — which it sort of is — or they think of opulent museum objects assembled from precious materials by the hands of magician artisans for dead tyrants or religions, like the exquisite but nonetheless gluttonous Dauphin’s Treasure at Madrid’s Prado Museum. But the decorative arts are where you get to see artists and artisans fly and see both taste and obsession unbound. They capture the whims of despots, powerful families, and strange individuals obsessed with beauty. They also capture the miraculous work of humanity’s greatest artisans. The decorative arts don’t have many fanboys these days under the age of fifty but they’re still everywhere around us, if you look. They continue in the work of artists like Stout, and they live through the commitment of luxury houses like Hermès who themselves walk a fine line between craft and ostentation (that’s a compliment), and who took Katie onboard as a one of their artist partners.

“Almost as a joke I was telling R & Company to call me a decorative artist,” says Katie. “Because I feel like it’s the bottom of the totem pole and the conversation about art and design is really tired. I love ornament. I’m sometimes disgusted by it. What’s appealing and what’s too much?” Stout is also aware of how her subject matter is often at odds with darker themes in her work. “A lot of people think my work is light and fun but often it’s the response to something dark. Like how comedians are often depressed. It’s sort of that. Hermès reached out to me and asked if I wanted to do a holiday window. We’d been talking for years and once you’re in their orbit they keep you in their orbit. They took me on a trip to Milan last year for Salone Mobile with my friend Mischa (Kahn) and a bunch of other artists and designers. You can commission anything you want through them. Like anything … the only thing they didn’t want was nudity (laughing). They’re really invested in making, they’re invested in the creative world around them and they’re invested in people.

During COVID they didn’t fire a single person. Isn’t that amazing? I’ve always loved the idea of making things small and then enlarging them because I think the scale is so wonky and uncanny. So, I made all of these little miniatures. We scanned them and then they were printed for the window.”

When we think about craft and the work of artisans it’s important to remember we’re largely talking about the work of women, especially in America. Stout’s work screams female, and it’s shoutout to the female hand and the female body is unique. What Katie does is so impressive to look at that a lot of folks who see her work don’t understand it’s importance because it’s cute. A short twenty years ago, work like this couldn’t have existed in the design world because it’s female abandon wouldn’t have been understood. Except perhaps by Murray Moss, but probably not by critics. Stout flutters between materials and sub- ject matter. Her work is confusing and fun. It’s more beautiful than work so crude should feel, and it’s sometimes sadder or heavier than what you’d expected from work so outwardly happy. Stout’s an exciting conundrum … she’s been positively described as subverting American craft.

An artist’s whim is a powerful thing. The power to pivot on an idea, a color, a smell, a disaster, or something that’s happening inside you or around you. Katie’s show last December confirmed how adept she’s become at pursuing hers. “With the recent Nina Johnson show I was pregnant while making it and I couldn’t use a lot of the materials that I maybe typically would have. I love learning about materials and using them. I really like experimenting. It was annoying. It wasn’t an intentional thing but, as I was making the work, a lot of it ended up being about pregnancy, and so a lot of things are bulging. I made a lot of things really big as I was getting big. The other thing that happened when I was pregnant was I got so fucking manic. My studio loved it. I started fixating on dogs. I just started making things with dogs. Now there’s the Dog Dog Dog Lamp. And then I made a blown dog in caged glass. Sometimes I will feel uncomfortable if something’s just purely sculptural. I made this piece recently and I was like, oh, it looks like it wants to be a fountain, but it wasn’t made in a material appropriate for a fountain. So sometimes I look at it and I’m like, I wish that was a fucking fountain.”

Katie Stout is repped by ninajohnson.com

Tony Moxham’s ceramic artwork for @MTobjects is represented by AGO-projects.com @AGOprojects Kate Orne is the founder and editor of UD.