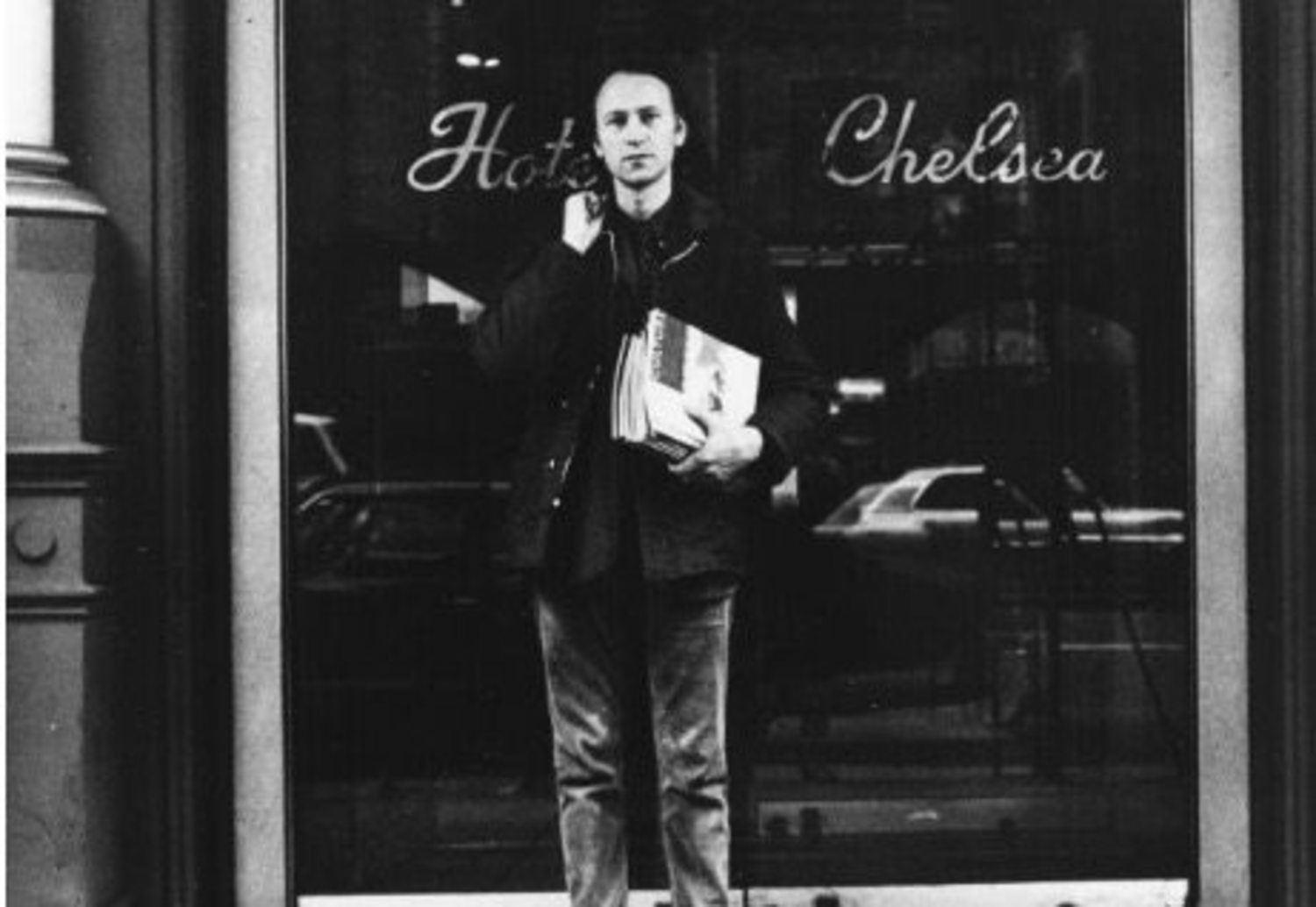

Jonas Mekas, Champion of the “Poetic” Cinema

By Richard Brody

Jonas Mekas was the co-founder, in 1954, of the seminal publication Film Culture. He was the first film critic of TheVillage Voice, and his self-chosen beat was the noncommercial cinema. Mekas founded the Film-Makers’ Cooperative and then, in 1970, Anthology Film Archives. He’s also a filmmaker. Any of these activities would establish him in the history books as one of the most important modern movie-people. But the activity that’s suddenly in the forefront is his critical writing: his “Movie Journal: Rise of the New American Cinema, 1959-1971” has just been reissued by Columbia University Press, and it’s a cause for celebration—and consideration. The original edition, from 1972, is long out of print. The book is a rich trove of cinematic wisdom, an artistic time capsule of New York at a moment of crucial energy, and a reflection of controversies and struggles regarding independent filmmaking that endure to this day.

Mekas, who is now ninety-three years old, was in his mid-thirties when, as he writes in the introduction, “I went to see Jerry Tallmer, at the Village Voice, and I asked him why there was no regular movie column in his paper. He said, why don’t you do one? I said, O.K., I’ll have it tomorrow.” That was in November, 1958. The book, Mekas says, features “approximately one third” of his Voicepieces. He also adds that he had a specific purpose in mind: “to take a sword and become a self-appointed minister of defense and propaganda of the New Cinema.” As a result, he writes, “I couldn’t afford wasting any of my space writing on commercial cinema. I invited Andrew Sarris, my co-editor on Film Culture magazine, to do that part of the job.”

Much of “Movie Journal” is indeed devoted to what Mekas considers the “New Cinema,” which is for the most part, but not entirely, what’s often called “experimental” films. He also calls it “underground,” “noncommercial,” and “poetic” cinema (as opposed to narrative films, which he calls “novelistic”), and “personal” cinema as opposed to “public.” His advocacy of these films—as he notes in a new afterword—has indeed withstood the test of time, thanks in large measure to his own exertions as a critic, programmer, distributor, and impresario.

As a critic, Mekas displays great antennae; he aptly perceives greatness where many others didn’t, and he vituperates against the judgment and priorities of the day’s high-profile critics (including Pauline Kael). The second sentence of the book, from February 4, 1959, reads, “We need less perfect but more free films.” Yet, that August, Mekas offers high praise to two modern European masterworks, Jean Cocteau’s “Orpheus” and Max Ophüls’s “Lola Montès,” the latter, the most expensive movie made in Europe to date. He wrote with discerning taste about some of Hollywood’s best directors (such as Howard Hawks, John Ford, and Alfred Hitchcock) and with nods of praise toward others among them, including Douglas Sirk, Vincente Minnelli, and Sam Fuller—and, in November, 1959, asserted, “Shoot all scriptwriters, and we may yet have a rebirth of American cinema.” (He also, in 1963, called for the shooting of all movie critics.)

Mekas instantly caught the brilliance of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” and wrote insightfully about many of his films, and about Michelangelo Antonioni (adding particular praise for “La Notte” and “L’Eclisse,” and devoting two columns in 1970 to “Zabriskie Point”), Roberto Rossellini (the films with Ingrid Bergman and “The Taking of Power of Louis XIV”), Jacques Rivette’s “Paris Belongs to Us,” the films of Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer (with special passion arising from his viewing of “Gertrud”), Glauber Rocha’s “Antonio das Mortes” and Miklós Jancsó’s “The Round-Up” and “Winter Wind.” He praises Akira Kurosawa’s “Drunken Angel” and Jean Renoir’s extravagant 1959 film “Picnic in the Grass,” albeit in terms that leave much out: “What does it matter what the film is about, its theme, its plot? It is about love, sun, trees, beautiful women, summertime, a picnic in the grass.” He praises Renoir overall and “Rules of the Game” in particular as “plotless.” As for Jacques Demy’s “Lola,” which he enthuses about, it’s “a film about the beauty of light.”

Read the full article here or in print.