Katie Stout, Tactile Recollection

Katie Stout

Tactile recollection

The space between memory

and reality underlies the practice

of the American artist and designer.

Furniture and domestic objects

take shape by combining trash

and heterogeneous materials

When I start a piece, I often begin by sketching,

typically with watercolours or whatever medium

is available. The less precious and the less control

I have, the better. I actively avoid looking at

reference images while I draw, instead relying on

my memory of what the subject looks like. I am

usually very, very wrong.

For instance, I recently made a ceramic frog

hugging a jug for an upcoming show, “Saint

Valentine”, at Nina Johnson. After sketching what

I thought was a sexy lizard climbing a jug, I

realised that it was actually a stoic frog hugging

a jug. From the sketch, I began making the piece

as I usually do, playing a game of “broken

telephone”. This game depends on the unreliability

of memory and progressively feeds off itself,

resulting in a reference that becomes increasingly

blurred and softer around the edges. The

morphing is only exasperated by the hand trying

to translate the image.

The space between memory and reality is where

the unexpected happens, revealing an off-kilter

truth; a boiled-down image that results in humour,

surrealism and caricature. This is where I find the

magic and joy in making. This is also why

I fell in love with clay. As a material, clay has an

exceptional propensity for memory, capturing

mistakes, energy and movements. It can vitrify

a spontaneous moment unlike any other material.

Fired clay remembers a person’s fingerprint long

after every other trace of them has been destroyed.

Materials with memories that capture

energy and motion give spirit to a piece that is

unattainable through machining alone.

I started making furniture after my mum died

when I was 20, and my brother and I had to

sell our house. I went through the Rhode Island

School of Design (RISD) without having a home

to go to, but like any reasonable person well

versed in darkness, I coped with humour, which

manifested in my work. Making furniture and domestic objects was a way for me to feel at home anywhere. Though I err on the side of

maximalism, I realised that even one small gesture

of domesticity can give a place the texture and

depth of a home.

I thought making things for other people meant

that a little part of me always had a home

somewhere, but then I realised that the feeling

of being an outsider is kind of liberating. You feel

like there isn’t much to lose, and you can play

with tradition however you see fit. I also think this

feeling of being an outsider is part of the reason

why I love trash. I see myself in it.

This strong empathy towards trash has made

me an organised hoarder. I see potential in every

scrap; detritus helps tell a story I could not have

conceived on my own. My studio is organised

with bins and bins of pieces loosely organised by

material, size and form. There are bins of ceramic

shards, ceramic flowers and fruits, glass flowers,

cast bronze cut-offs and tons of fabric (some of this

is arguably not trash). I save pieces with appealing

textures and colours for my “stuffed scrap chairs”

and other quilted projects. I’ll save every last piece

of fringe or pom-pom to use in ceramic burnouts

where I dip fabric into slip and make things like lampshades or other drapey forms that are unattainable by hand. Old, dried flowers from

bouquets past will be memorialised in clay and

used in fruit ladies or chandeliers. I sift through

pieces like I would at a bargain bin and build them

into new work like a quilt. The “patch vessels” and

“flower vessels” are the best examples of this.

I use a similar method for fruit ladies. I build most

of the fruit beforehand (without looking at images

of fruit) and then put them together like a puzzle,

often beading them through metal, depending on

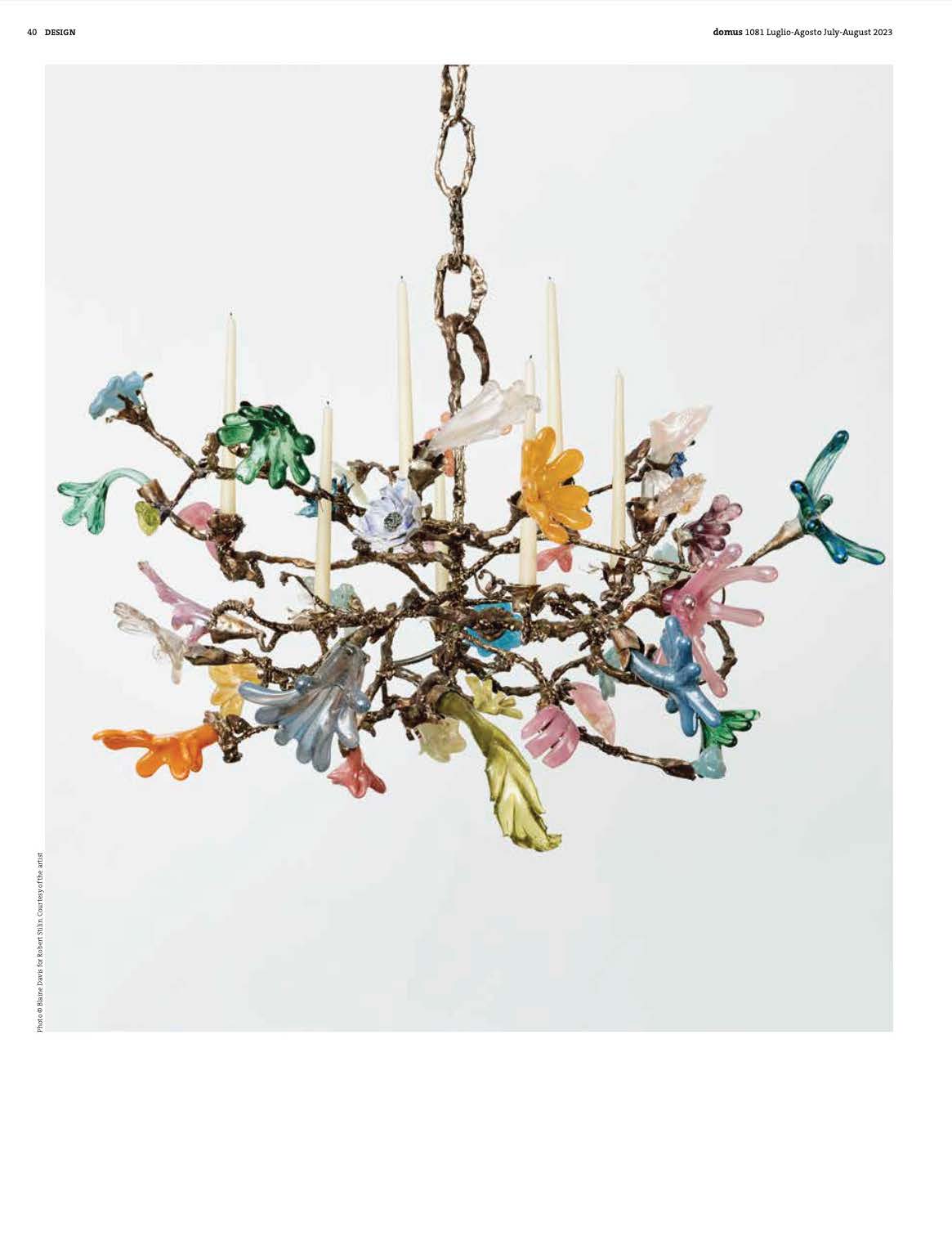

the scale, to make a fruit lady. I pick and choose glass flowers and produce to create Murano- inspired chandeliers. Scraps of bronze provide important textures and I paint the branches

with hot bronze goo from the MIG welder. Often,

I’ll throw in a few misfit ceramic pieces as a

counterbalance to the pretty and pristine glass.

Papier-mâché will forever and always be my

favourite material as it is pure trash. I love using

old notebooks, checks and receipts (anything

with banking information) in a piece. I typically

make shelves out of papier-mâché because it

seems appropriate for the storage of books and

knick-knacks. I recently moved my studio into an

old church upstate and found all of the church’s

accounting – I saved it for this exact purpose.

People often ask me why I make work that

functions. The simple answer is that I like it when

things are used. Whenever I buy something,

I always imagine what it will look like filthy, with

my personal patina, and that’s the determining

factor. I want these pieces to have a life after me

and for people to tell their story with them.

If something breaks, then kintsugi. Every mark

holds a memory and tells a story. I make a lot of

lady lamps with bronze touch switches as nipples,

and nothing satisfies me more than seeing the tip

of a nip polished from healthy use.

Edited by Toshiko Mori in the July/August 2023 1081 Issue of Domus.