Painting motherhood: Madeline Donahue

By Nadine Zylberberg

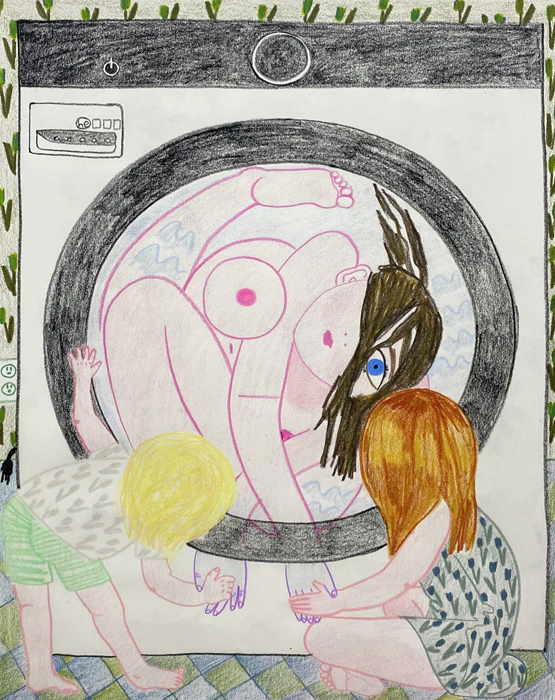

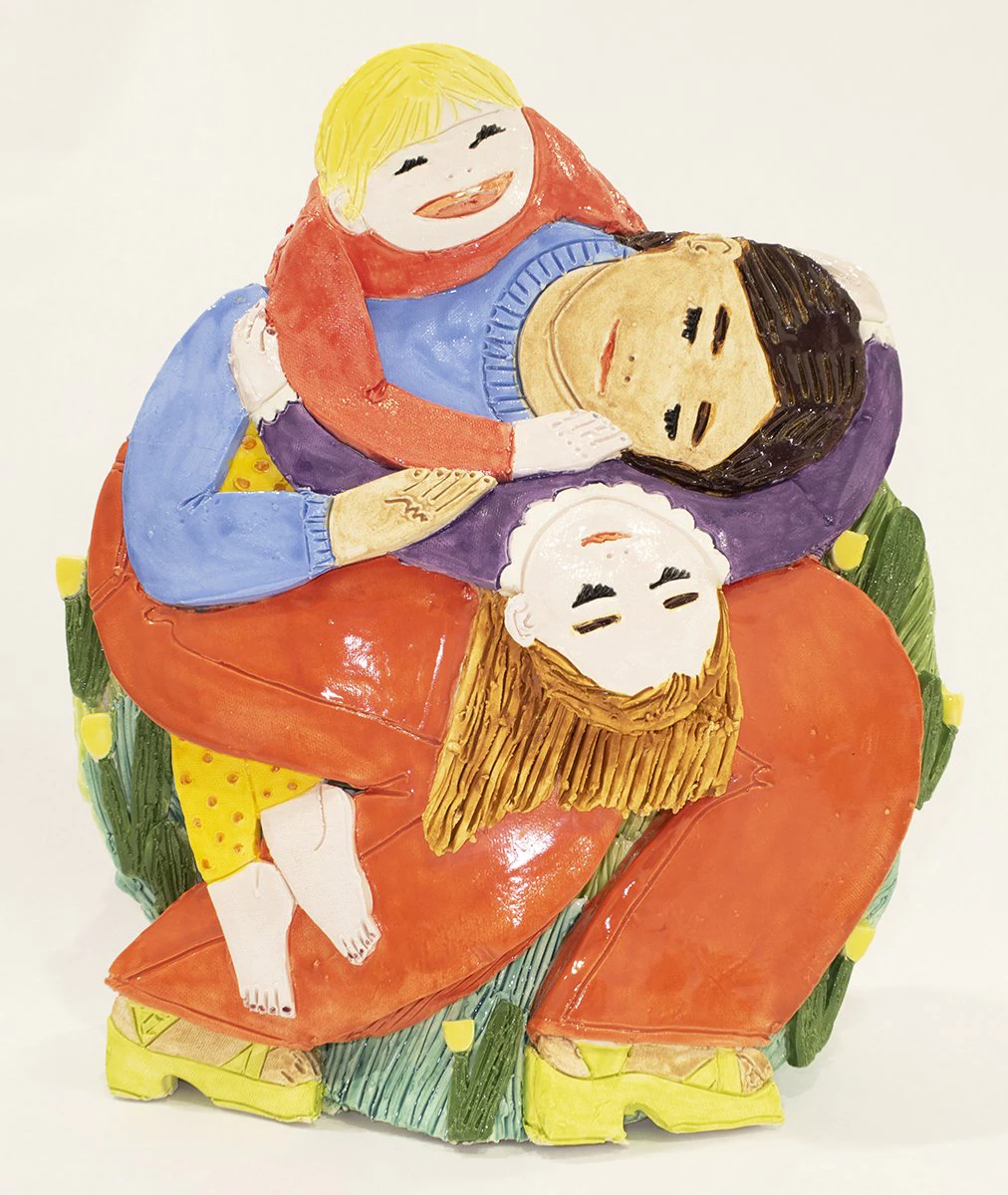

Hello there! This week’s newsletter looks a little different. I won’t be sharing articles or recipes or links, but something better, something a little deeper. Once a month, I’ll be devoting All’s Well to conversations with creative women who inspire me. First up, Brooklyn-based artist Madeline Donahue. I was immediately drawn to Madeline’s work for her intimate, honest, at times chaotic, portrayals of motherhood. As a new mom myself, I’m realizing how rare it is to find representations of motherhood in our culture that feel authentic to the messy, yet beautiful, experience of it. Madeline’s paintings, ceramics, and drawings encapsulate just that. Now more than ever, as my mind reels in despair over the idea that a woman’s autonomy—her decision to be a mother, and when and how—would ever be in question, these representations matter.

Madeline began painting in her teens and, after years of freelance work with artists, earned her MFA from Brooklyn College and embarked on a new creative journey, along with a personal one as a mother of two kids, ages six and two. Below is an edited and condensed version of my conversation with Madeline about what inspires her, why she favors bold colors, and how motherhood has changed her. Plus, a look at her vibrant work, some of which is on display now as part of Johansson Projects’ summer show, Community Garden, in Oakland, California.

How did motherhood become a central subject in your work?

I feel like this is work I’ve been making my whole life. I went to an arts high school and started painting there. The first real painting I made, when I was 14, was a portrait of my mom holding me. It was a 6×4-foot painting. I ended up doing a lot of portraits of people in my family: I painted my mom pregnant, I painted my dad holding me as a baby. There was something healing about it, showing people these portraits. There was a lot of love in it. [Over time, I became] bored with religious imagery of mother and child, and bored with portraiture of seated figures and passive women. When I started grad school, I had just had a baby and I was secretly making work about motherhood and hiding it in my studio. People I was working with found it and were like, “This is really genuine. This is the stuff that’s way more interesting.” I had really great people around me to help me get rid of the artifice around making work. This is the work that came out of that exercise in opening myself up to being vulnerable. Because I’ve been in the depths of babies and little kids for the past few years, it’s just been really natural.

What inspires your pieces?

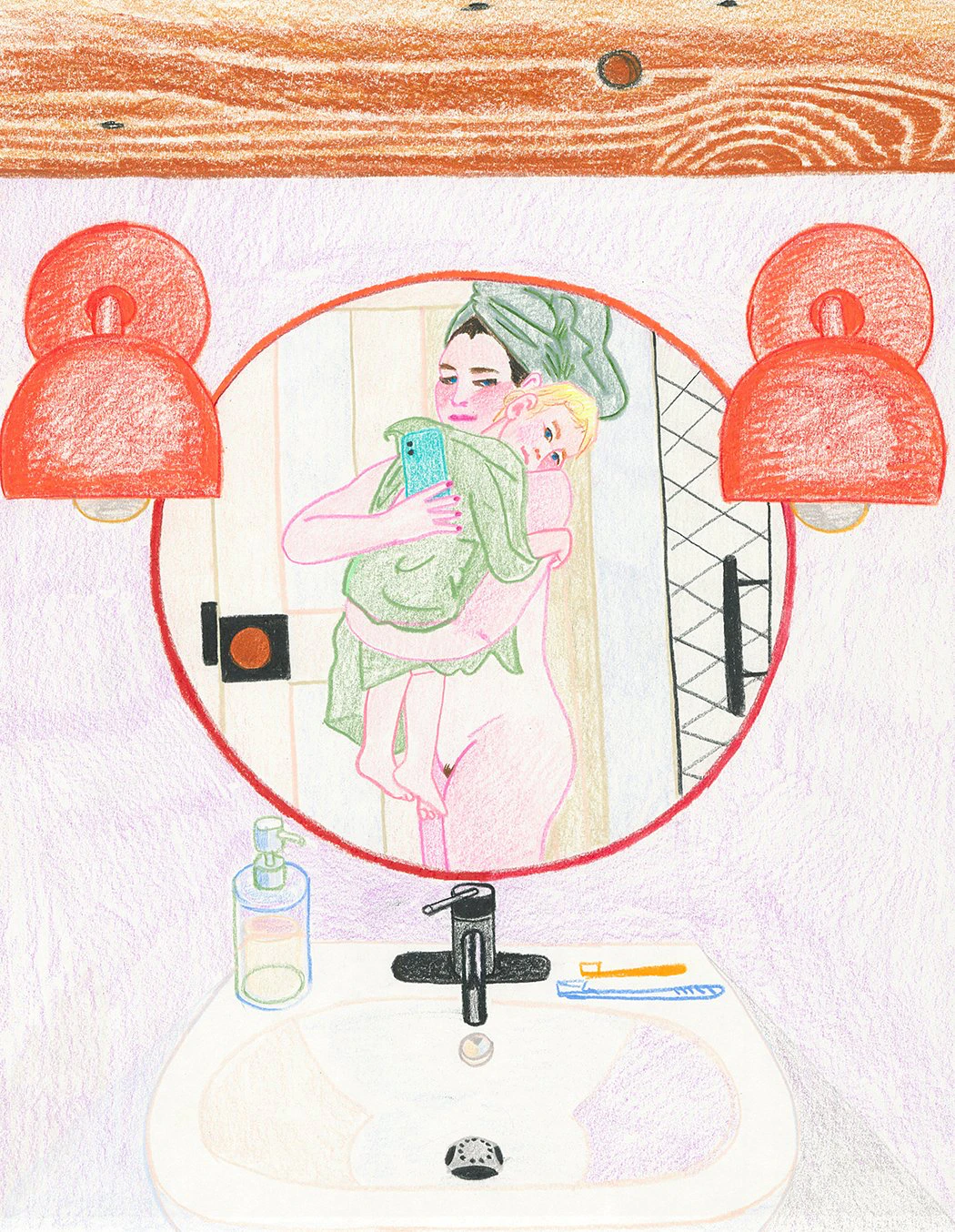

A lot of the work comes from shame, from the situations that are just so ridiculous, for instance, trying to go to the bathroom and having a baby—or two babies—literally cry and scream at you because they need you to hold them right now. They don’t care where you are or what’s happening; the only thing that matters is that we are together. That is so funny to me. It’s crazy how long it took me to just embrace that, to recognize how unique that was as an experience. I’m really motivated by the darker places, the darker feelings. And for some reason, my reflex is to make fun of them. The really hard stuff just makes me laugh more than feel bad.

Was it instinctual to turn to bright colors and humor, or was that a process?

I’ve always been into really bold, beautiful colors. I feel like so much of life is gray and dull, and people are so afraid of expressing color in their clothing or the appearances of things in the world… It’s just boring to me. I’m really interested in how simple bright colors can be. I think it also makes sense in the work because there’s something a little bit offensive, almost too forward, about bright color. Because so much of this experience is about being a hidden person doing this invisible work, it makes sense to have it be bright. There’s nothing serious about it. It’s very clear, looking at the images, that they’re about fun and chaos and joy, and that’s expressed through the color and also through the way that I’m making the work. I’m making the work quickly and it’s fun to make. I’m not lingering too long on any line or anything. It’s just happening and it’s done.

Is there a particular piece that you constantly return to?

One of the first paintings I did in this series of work is called Cyclops. It’s a 16×20-inch painting of a mother where the baby is wrapped around her head, covering up her face, except for one eye. I think about that painting all the time. I wish I could re-experience making it. I remember painting it quickly in an afternoon, and loving it, loving the colors of it. The way I was working then is I would have the drawing, I’d go to my studio, I’d paint it in a couple hours and then I was done with it. The next day, I’d do something different, so it was super fresh. The simplicity of this one painting has connected to so many others. A lot of the work has the repetition of this one eye. I really love that as a symbol, relating it to mythology, relating it to the evil eye, connecting it to Egyptian hieroglyphic eyes… all the symbolism that can go into it is just endless, like a well of fun to think about making work from.

As a very hands-on parent, what does work look like for you? How—and when—do you make space for it?

I very consciously became a parent. It was something I wanted to do. I took time, planning, thinking about what kind of parent I wanted to be, what my goals were… So by the time my first daughter was born, my focus was to be calm and to be present when I was with her. When I was home, I was focused on being a parent, and when I was in my studio, I was just a workhorse.

With my second now, after living in COVID for two and a half years, it’s total chaos. When the pandemic started, we went up to Connecticut to stay with my in-laws, just to be able to be outside more, and that’s really when I shifted gears. I would set up my materials in the morning on the dining room table at my in-laws’ house, and then would work throughout the day. Now, I kind of work all the time—even though I’m home with my kids most of the time. I think it’s really good for kids to see their parents work. It teaches them how to be adults. I love having a life where I get to be an artist and can work whenever I want. I can leave to go participate in my kids’ lives and I can come back and work. I love the back and forth.

I think parenthood has made me really good at dropping everything other than what’s right in front of me. So if I’m with my kids, I’m not thinking about anything else; if I’m working on a project and I have time to myself, even if it’s 15 minutes, I can just devote my brain to that.

Can you give us a snapshot of life as a parent and how it translates to your art?

Anything I feel bad about, I think about in my work. Like bath time. A bath is never just a bath. For me, bath is two kids who have to not drown in the tub, who hopefully won’t fight the whole time, and maybe someone can get their butt cleaned. Every moment has so much anxiety built into it—and also so much joy. And then you sit down to supervise, and you really just want to sit on your phone and look at whatever’s happening in the world. It’s also a time where you kind of feel like you get to connect to the outside world.

How has motherhood changed you?

This is something I’ve been thinking a lot about recently. The bond between a baby and mother, in my experience, is almost a superpower in the sense that it protects you from these outside influences that can affect your self-esteem. I think in any industry, there’s a lot of anxiety to be competitive and do what everybody else is doing so that you feel like you’re cool and beautiful and capable and successful. Something about having little kids created this bubble that kept me from caring about any of that stuff.

It happened to me when my daughter was born. I didn’t care if I was invited to parties, I didn’t care if I was invited to openings, I didn’t care about what my friends were doing in their careers, because I had this bond with this baby. I just honed in and focused on the intensity of love. I’ve started to notice that, as my daughter is getting older, that superpower is kind of wearing off. I’m being thrust back into the world and it’s like, “Oh, where do I stand? Who am I in terms of other people and where do I exist in the world?” Right now, I’m working on maintaining that focus on what’s actually important to me instead of what I think is important to me based on what’s around me.

In what ways has motherhood surprised you?

The life I had before doesn’t mean anything to me. I’m just completely in love with these people that I didn’t know before. Any of the expectations I had for my life before they were born don’t matter. Also, the strength of my body is something I totally underestimated. And my ability to do what I want to do with a tremendous amount of limitations and stress. Because I have this intense love for these people, it’s an incredible motivator to do other stuff that I love to do.

Well said, Madeline.