Terry Allen’s “Some Pictures and Other Songs”

By Rob Goyanes

Terry Allen was born in 1943 in Lubbock, Texas. His parents represent two archetypes of American mythology: a baseball-playing father and a jazz-pianist mother, kicked out of college for playing “devil’s music.”1 As a teen, Allen was enamored with the beatnik scene when it appeared in Lubbock—everyone started wearing sunglasses at night2—and went on to study at Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. His record Juarez (1975) is a masterpiece of countercultural country, a song cycle with a cast of characters that cross state and bodily borders: they fuck, fight, flee, and die. An outlaw of the outlaw country scene, Allen is perhaps best understood as a conceptual artist, using Americana to create everything from sculptures and installations to theater.

“Terry Allen: Some Pictures and Other Songs,” at Nina Johnson, consists entirely of drawings, all from 2019. In Storm on the Ghost of Jimmy Reed, Allen presents the bluesman Reed with a mustachioed, half-faded face. A text in the bottom-right of the drawing reads: “When we were kids one Saturday night when it was storming they snuck us in the backdoor of the Cotton Club and let us peek in at him from the dressing room door behind the stage. He was slumped over in a metal folding chair slurring out his deep slow hypnotic heroin groove. You could see one blue light shine on top of his nearly bald head. A large woman wearing a gold dress and green high heels was standing behind him bent over whispering lyrics in his ear while he was nodding out a harmonica ride.” From Allen’s ongoing “Memwars” series, it’s a colorful yarn braiding music history and personal memory. The cheeky portmanteau memwar reflects Allen’s way of lamenting wars foreign, domestic, and class-based. He doses his art with enough bittersweet humor to highlight the absurdity of conflict—and maybe make it a little easier to think about.

In Forever Man, a blurred image of a soldier contains the words: “NOW,” “THEN,” “EVERYWHERE,” and “ALWAYS.” Resting above his right shoulder is a snake with its forked tongue out and a donkey with a naughty look on its face. The Vietnam War, at full tilt once Allen’s career began, was his fulcrum. His body of work titled “Youth in Asia” (1983-1991) dealt with the war’s aftermath, in part a memorial to those soldiers who committed suicide. These days, Allen seems to view war not as a discrete series of conflicts but as a cohesive, eternal machine. As he laments on his newest record, Just Like Moby Dick (2020), “It’s just the war, same fucking war, it’s always been.” Memoir, in Allen’s phrasing, is a form of war, a never-ending conflict between nostalgia and trauma. In Longing, a white sperm whale (presumably Moby Dick) lies beached, spraying blood from its blowhole, on the front lawn of a house against a black background that threatens to engulf it.

Tragedy and comedy are guiding points on Allen’s aesthetic compass. In Study for LIARLAND, a group of Disney characters suffer from Pinocchio’s moral-physical pathology: Mickey Mouse, Snow White (labeled “So White”), The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) author Carlo Collodi, and Walt Disney all have the long noses of a liar. Indicating Allen’s occasional tendency to push into cloying, obvious territory, puppet Pinocchio has a raging, erect nose shooting out the fly of his pants, while human Pinocchio gets strangled by his own schnoz. Exaggerating cartoon tropes to critique American power is a tired strategy—but a picture with a psychedelically superimposed Homer Simpson, Blind Homer’s Hands/Notebook 3, is compelling: a figure of buffoonery that you love to hate.

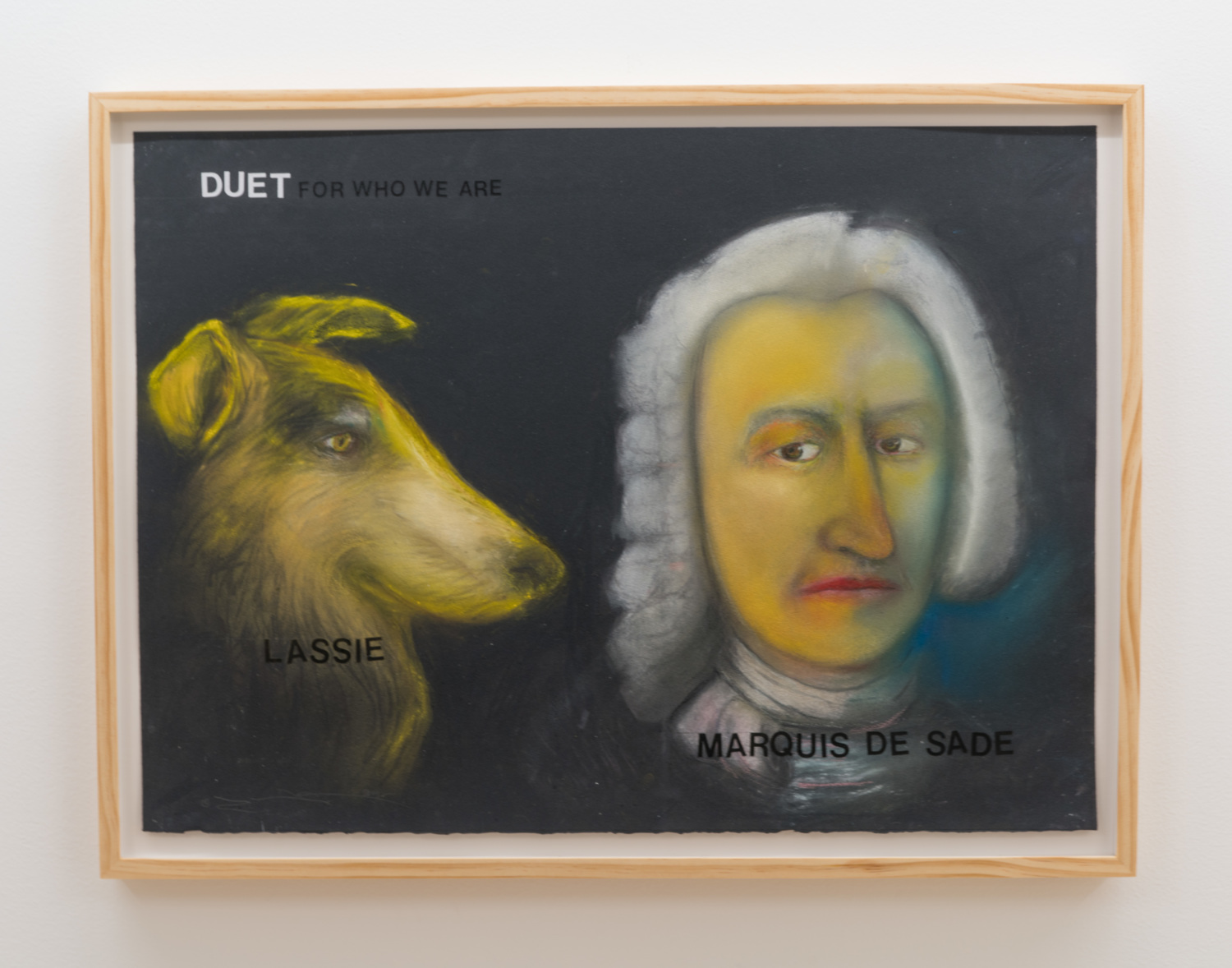

Allen’s work is better when it winks, rather than smirks. In Wall, Earth and the moon are separated by a brick wall. Rather than militarized separation and restrictions on freedom—there is no doubt that Allen is anti-wall—the first impression is of a tower connecting the two. Such comedic torquing can enter corny or cliché territory, but it’s at its finest in works like Duet: a portrait of Lassie and the Marquis de Sade, the innocent heroic and the pornographic criminal side by side. Characters in time and place, the use of storytelling to flesh out our complex selves—these are what makes Allen’s work so resonant. His creative universe, reflecting our own, is a litany of junkies and cops, quadruple amputees and peyote eaters, lovers and killers. The show functions best as an invitation into his world, rather than as a mirror to topical issues. After all, it’s just the same fucking war.